PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

Lyttelton Town Section 1 (TS1) and the Canterbury Hotel

By JC Betts

In 1850s Lyttelton, Norwich Quay was often called ‘the Beach’. On the south side was a rocky shore, with a sandy stretch opposite the first hotel in port, the Mitre, useful for beaching boats and waka from Ōhinehou, the kāinga at the western end. The early settlers cooperated to net impressive hauls of fish off this beach, but during the 1860s it and the kāinga disappeared under reclamation as the railway and tunnel were constructed.

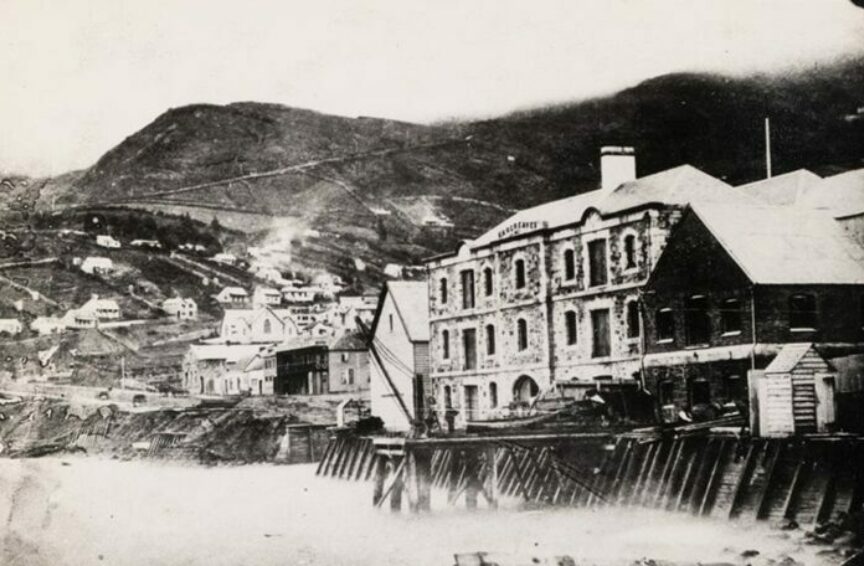

Towards the eastern end of the beach Captain Thomas had a wharf constructed, extending out from the bottom of Oxford Street. The Canterbury Association Store was built alongside, the only building on the south side of Norwich Quay. This store was later replaced by an impressive brick Post Office incorporating customs and telegraph services. This was the point of entry to Canterbury for all travellers and communications from the outside world.

The north side of Norwich Quay was subdivided into quarter acre town sections for distribution among the colonists in February 1851. Land was priced at £3 per acre (approx NZ$1,050 today) and each settler was entitled to one town section and 50 rural acres. Early investors in the Canterbury Association were often wealthy supporters of EG Wakefield’s colonisation plans who never intended to become settlers themselves and used agents in New Zealand to act on their behalf.

The first of these investors was Maria Somes, widow of the shipping magnate Sir Joseph Somes, who had supplied all the vessels for the New Zealand Company settlements. Having first choice, Maria’s agents JR Godley and WG Brittan selected the most valuable section in Canterbury, Town Section 1 (TS1) on the corner of Norwich Quay and Oxford Street. For her 50 rural acres they chose the area directly above Lyttelton, north of Ripon Street.

Maria never came to New Zealand but conveyed her property to Christ’s College “as long as the said college shall continue in union with the Church of England“ to endow scholarships, which continue to this day. The school began in 1851 in the Lyttelton Immigration Barracks with five pupils and moved to Christchurch in 1852. Somes and College roads in Lyttelton commemorate Maria’s generosity. In the dining hall of Christ’s College, among the portraits of distinguished greying gentlemen, is one of an attractive, dark haired woman in a red dress – it is Maria Somes, and she deserves her place of honour.

What would Maria have thought about the use made of her gift? TS1 became the site of the Canterbury Hotel (originally called the Canterbury Arms). Richard Davis is named as the first leaseholder but his father Rowland was more closely associated with the business. An Irishman, Rowland had emigrated to Wellington with his family in 1840 and became involved in the hotel trade, establishing a Working Men’s Association and an Oddfellows Lodge before his move to Lyttelton.

Rowland Davis was a candidate for the Lyttelton electorate in the first parliamentary election of 1853 but withdrew at the last minute, to the relief of Henry Sewell, the lawyer who came from England to wind up the Canterbury Association. Sewell wrote:

“Davis is merely a vulgar, pushing fellow whom it would have been absolutely discreditable to send up to the General Assembly as representing the social superiority of the Canterbury Settlement”.

Ed W David McIntyre, The Journal of Henry Sewell 1853-7 Vol I, 1980, p. 362.

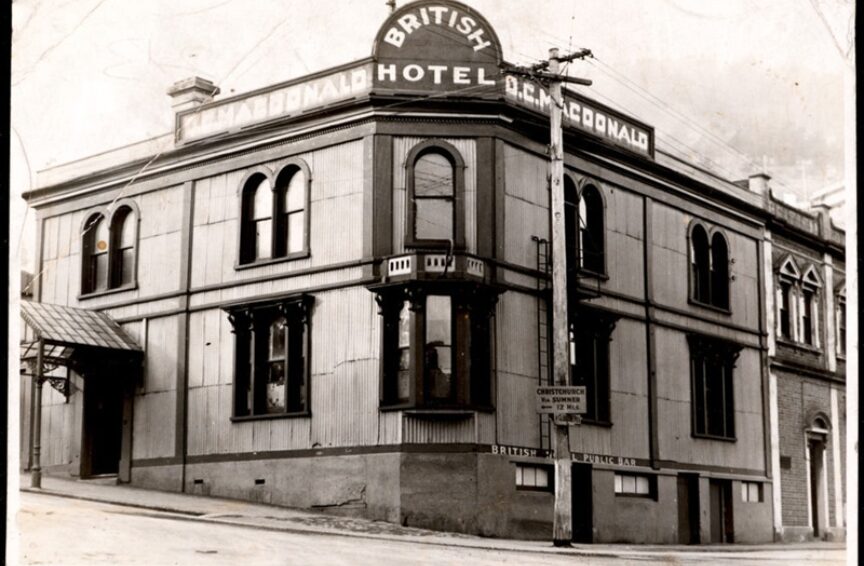

As the port grew, and with everyone reliant on sea transport, business at the hotel boomed. By the 20th century the Union Steamship Company’s interisland ferry service was bringing hundreds of travellers from Wellington at seven o’clock every morning, and as many left every evening, until the end of the service in 1976. The Canterbury Hotel, closest to the ferry terminal along with the British Hotel on the opposite corner, sold 300 breakfasts some mornings in the 1960s.

There have been three hotel buildings on the site. The first was built of timber and burnt down, like everything else in Lyttelton’s central block, in the fire of 1870. The second hotel was replaced in the 1920s, after a smaller fire, by an imposing brick edifice with a battlemented parapet. Then, in February 2011, following Canterbury’s devastating magnitude 6.4 earthquake, the Oxford Street frontage was in heaps on the road, the interior on show like a messy doll’s house. Demolition followed in July 2011.

The Canterbury Hotel occupied only the corner of the quarter acre site. On the rest of the section, which extended up Oxford Street half way to London Street, many smaller businesses came and went. The first edition of the Lyttelton Times was printed in a shed on the property in January 1851. Over the years, private houses, stables, chemists, drapers, ironmongers, coopers, tearooms, bakers, tattooists, restaurants, lawyers, newspaper offices, bookshops, barbers, and more have occupied TS1.

It seems miraculous that the building known locally as the ‘Tin Palace’, the 1871 office of Duncan Cotterill’s legal firm, survived the earthquakes, the only building on TS1 to do so. The materials and style – vertical corrugated iron with carpenter gothic details – were very popular after the 1870 fire for those who could not afford brick or stone, to the extent that the port was nicknamed ‘Little Tin Town’. Even buildings with impressive frontages used corrugated iron for the side and rear walls.

Today, the site, once the most desirable spot in Canterbury, has been on the market for quite some time, but there are no buyers as yet.