PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

Cass Bay Motu-kauati-rahi

The bay between Corsair Bay and Rāpaki (home of Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke), was named by the Ngāi Tahu chief Te Rakiwhakaputa as Motu-kauati-rahi, which means great fire-making tree grove, distinguishing it from neighbouring bay Motu-kauati-iti or little fire-making tree grove (Corsair Bay). Both were host to stands of kaikōmako (Pennantia corymbosa) trees which were essential in the process of making fire. The soft wood would be rubbed together with either māhoe whitey wood (Melicytus ramiflorus) or patē seven finger (Schefflera digitata); the friction producing the sparks which could ignite flame.

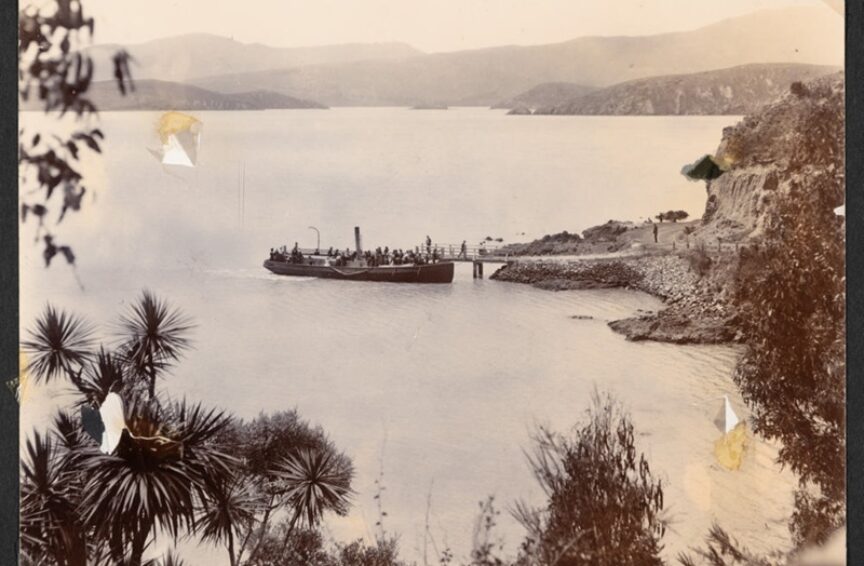

The bay acquired its English name in the early 1850s, after surveyor Thomas Cass. Born in Yorkshire in 1817, he was educated at the Royal Mathematical School and served a seven year apprenticeship as a mariner. Cass first spent time in New Zealand in the early 1840s surveying in Auckland and Northland, and was involved in conflicts with Te Rauparaha at Kororareka Russell in 1846. After time at sea on the brig Victoria and a return trip to England, Cass arrived in Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour on 15 December 1848.

Cass was tasked with surveying the proposed new Canterbury Association settlement under chief provincial surveyor Captain Joseph Thomas and alongside Charles Torlesse and Henry Cridland; most notably he charted the harbour itself. Upon Thomas's sacking in 1851 by Canterbury Association agent John Robert Godley, Cass succeeded him in the role. For a time he based himself with Torlesse and Cridland in the sheltered bay that would come to bear his name, before moving to what was then referred to by the English as Erskine or Cavendish Bay, now Ōhinehou Lyttelton.

In 1852 Reverend Edward Puckle pre-purchased 50 acres of freehold land in Cass Bay from his home in England, arriving in 1850 on one of the ‘First Four Ships’, the Randolph with his wife and children. After watching much of his 70 tonnes of furniture drift out on the tide from the beach at Cass Bay, Puckle sold the land. His lot was taken over by E Salt to provide grazing pasture to stock owners. Throughout the late 1800s the bay was worked by a number of other farmers; Richard May Morten, and dairy farmers John Webb and Roderick Gallagher.

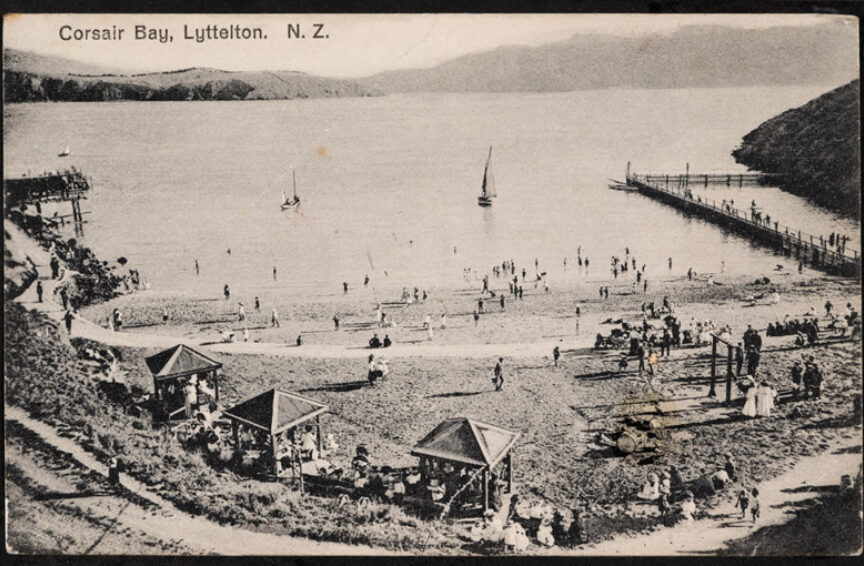

As early as 1851 butcher George Hunt was recorded as working at Cass Bay; Garfort and Lee, Owen and Dyer, and the aforementioned Morton were also licensed to operate as slaughtermen in those early days. In 1902 the Lyttelton Borough Council, having purchased this section of land, approved plans for a public abattoir. From 1875 there had been an abattoir at neighbouring Corsair Bay which was closed in 1884 due to the popularity of that bay for swimming. The Cass Bay abattoir included a slaughterhouse and drafting pens and yards for sheep, cattle and pigs; this facility continued in operation until its closure in 1964. In the mid century the slaughtermen included Jones (nicknamed Bones!), MacDonald (Mac) and Wells and the bay was referred to as Abattoir Bay or Blood Bay; local lads were drawn to watch sharks feeding on the gory discharge into the water. The bay was known by several other names over the years – Sandy Bay, Flea Bay and Lady Bay.

Since 1930, due to a shortage of state houses in Lyttelton, the Lyttelton Borough Council had been looking for land for subdivision since; Cass Bay was mooted for development of a ‘model’ suburb. However the interruption of WWII put such ideas on hold and the Cass Bay Mine Depot was developed by the RNZN in 1943, in part attracted by the fact that the bay was largely uninhabited. The complex included brick and concrete magazines, an ammunition processing building, administration buildings, a four‐man hut, guard house, flag station and even a naval gun adjacent to the road, which necessitated a naval escort through that stretch. After the war the obsolete post was used by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) and subsequently by the Navy League Sea Cadets, the TS (Training Ship) Steadfast unit – a story for another time.

By the time these photographs were taken mid to late 20th century, the bay was all but denuded of vegetation cover and its relatively flat contours were ideal for residential development. In December 1975, post the opening of the Lyttelton road tunnel and consequent improved connectivity to Christchurch, plans for a modern subdivision were released, with sections costing between £650 and £1400. The bay has developed over the years to become today's well manicured suburb, with strikingly modern buildings like a somewhat contentious Michael O'Sullivan designed copper house, which flanks the access to popular recreational water and walkways.

Thomas Cass's later years were marred by ill health largely due to asthma, leading to his death aged 77 in 1895. He is buried alongside his wife Mary (they had no children together, though he was stepfather to the children of her first marriage) in the Barbadoes Street cemetery in Christchurch. His name also lives on in street names in Christchurch and Timaru, in the settlement of Cass in the Selwyn district (the much loved 1936 painting by Rita Angus of the Cass railway station is an icon of New Zealand landscape art), in the Cass River nearby and in Ōrongomai Cass Peak behind Ōhinetahi Governors Bay, which is crowned by a 1980's radar dome, part of New Zealand's air traffic management system.

See Jane Robertson’s excellent survey of Motu-kauati-rahi Cass Bay