PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

The Corsair Bay Baths

According to certain ancient narratives of Aotearoa, Mahuika, the goddess of fire, threw her last spark into the kaikōmako tree to keep it safe from her grandson Maui’s deceits to acquire fire for himself. To escape his grandmother’s anger, Māui transformed into a hawk and made a desperate plea to the god of storms, Tāwhirimātea, whose deluge protected him from her fiery wrath. Mahuika’s last flame was safe, however, in the form of the kaikōmako tree through which Mahuika gave the people the means for fire-making. Three centuries ago, the great Ngāi Tahu leader Te Rakiwhakaputa, on passing through what many now call Corsair Bay, gave it the name Motu-kauati-iti, the little fire-making tree grove, owing to the treasured kaikōmako trees there that early Māori used to reignite Mahuika’s fire.

In the years following the Canterbury Association’s purchase of the Canterbury Plains outside Whakaraupō, Motu-kauati-iti acquired the Pākehā name of Corsair Bay. On the 23 April 1861, a strong south-wester caused the steamship Omeo to drag her anchor chain off Naval Point, tangling with Captain Thomas Gay’s whaling brigantine, the Corsair, which was set adrift in the gale. The sailing ship was wrecked on the rocks in the small sandy bay around the corner, and this corsair gave its name to that place.

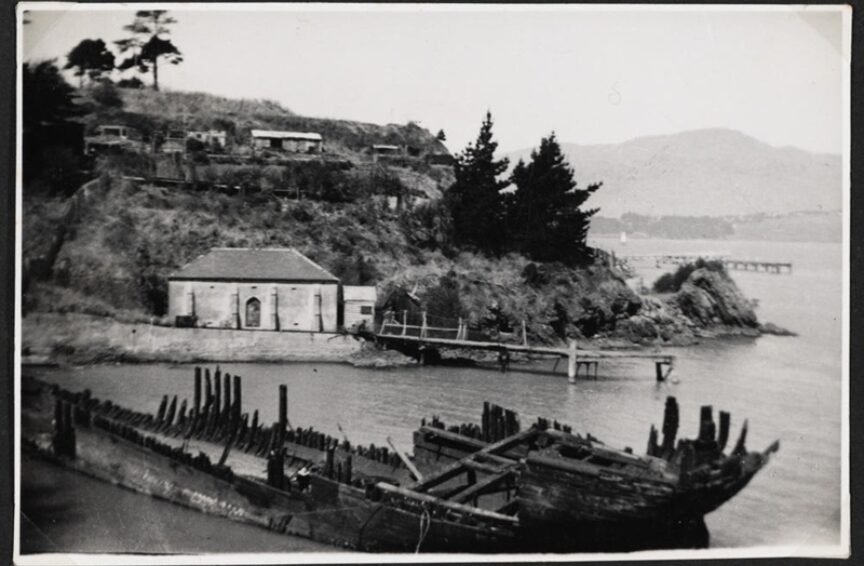

Corsair Bay, largely stripped of its kaikōmako (Pennantia corymbosa) groves, was by then already in use for shipbuilding and subsequently became home to several enterprises including: Malcolm Miller’s shipyard and slipway from 1874-1907; an abattoir in 1875 which moved to Cass Bay next door in 1884; and William Langdon’s, later Prisk and William’s, brick kiln which was still in operation in 1906. And for a time, the Lyttelton Rifle Club, formed in the 1860s, operated a shooting range in the bay.

The quiet, sheltered and rather beautiful swimming beach has been popular with locals from at least the 1880s on, with Christ’s College and Christchurch Boys’ High swimming sports being held there from 1886. The bay’s popularity as a swimming destination increased markedly in the early 1900s after the Dampier and Sandy bays in Lyttelton were incorporated into the fast developing port. And in 1905, the Lyttelton Borough Council passed a bill in the Parliament to gazette the Corsair Bay Recreation Reserve ‘as a pleasure resort for the public of Canterbury’.

This pleasure resort rapidly took form in the following two years, 1906-7, as 24 prisoners from the Lyttelton Gaol hard labour gang were put to work clearing rocks, building the sea wall, and forging the promenade walk around to the Lyttelton Domain. A 24 m jetty was built, followed by a playground, pavilions, and a women’s bathing enclosure with accompanying, discreet ladies’ dressing sheds and steps down to the bath. Apparently the enclosure kept the sharks at bay, attracted as they were by the Cass Bay abattoir that discharged its bloody offal directly into the harbour waters!

Following complaints regarding certain rowdy young men making use of the ladies’ baths, indecently clothed and of rather coarse manners and tongue, the Lyttelton Borough Councillors promptly passed a 1908 bylaw to enforce ‘the decent and orderly control of Corsair Bay as a pleasure resort’. A men’s dressing shed and diving platform were subsequently built on the opposite, eastern side of the bay, the piles of which can still be seen today as one walks down the path towards the beach.

These additions – along with boys’ and girls’ dressing sheds, a raft in the centre of the bay, and a caretaker’s cottage – transformed Corsair Bay into Canterbury’s premier beachside playground through the 1910s into the 20s and 30s. Crowds would flock into Lyttelton on a summer’s Sunday via the train, and then promenade in their finest wear around the coastline walkway, or climb aboard an alarmingly overcrowded ferry. The steamship SS Purau began a ferry service in 1909 and by the 1920s several ferries were competing for the lucrative summer trade, sometimes even bumping hulls to make first berth, or so they say.

By 1921, the crowds were becoming excessive with reportedly up to 2500 people cramming onto the beach and in the water. The 1922 bus service from Lyttelton didn’t help the matter, but the newly formed Corsair Bay Swimming and Life Saving Club certainly helped to keep the bay safe for swimmers. The Corsair Bay beachside pleasure resort remained a popular Canterbury summer destination for generations of Cantabrians through into the 1960s. Then, presumably with the rise of the personal automobile and increasing recreational competition, not to mention rising maintenance costs for Council, the big crowds faded away and the facilities slowly degraded back into the sea.

Nowadays, only the seawall, a raft and one jetty remain, alongside the remnants of the old diving jetty and men’s huts. But far from being a mere shadow of its former heyday, today’s Motu-kauati-iti Corsair Bay remains a secluded and very pleasant swimming beach of a summer’s day in Whakaraupō.

See also Jane Robertson’s excellent history at http://lytteltonharbourjetties.blogspot.com/2019/06/corsair-baymotukauatiiti-1.html