PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

Turning sea into land – reclamation in Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour

The foreshore and seabed of Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour have been significantly altered by human endeavour over several phases since the first days of European settlement in the region.

The harbour was known to local Māori as Whakaraupō – ‘harbour of raupō reed’ for the extensive stands of bulrush (Typha orientalis) growing at the head of the inlet, which were used in the construction of whare. In the late 1820s it was known to the English as Port Cooper, so named by sealer and flax-trader Captain William Wiseman. In 1848 the harbour was called Port Victoria for a short time, at the suggestion of Captain Joseph Thomas, surveyor for the Canterbury Association. In short order the harbour was renamed again in 1857 as Port Lyttelton after George William Lyttelton, the Fourth Baron of Lyttelton and Chairman of the Canterbury Association from 1848-1852.

Within this harbour of many names lay the shallow bay which would become the port of Lyttelton. In 1850 Captain Thomas and fellow surveyor, Thomas Cass, named it Cavendish Bay after Canterbury Association member Richard Cavendish, a friend of Association founder, John Robert Godley. Confusingly, the appellation Erskine Bay was also used in this period, honouring Captain Erskine of the frigate HMS Havannah, flagship of the Australian Division of the Royal Navy’s East Indies Station, which visited in 1851.

The bay was shallow with a sloping foreshore and a seabed of soft marine sediment which would prove a significant challenge to work with. The first phase of reclamation in the1860s utilised rock and fill from the excavation of the Lyttelton Rail Tunnel. The intention was to extend the waterfront into deeper water to allow for deep water jetties in order that ships could berth close to shore rather than having to moor at sea. The new land would support the demands of increasing numbers of cargo vessels, with railway yards, goods sheds and sidings to manage the movement of freight.

The rail tunnel construction which began in 1860, was slowed for a time when rock that was harder than anticipated was encountered, requiring more money to be raised to attract new contractors. Successful completion in 1867 was a world first in that the tunnel was driven through the rim of an extinct volcano. It provided a vital link to the developing city of Christchurch and the wider Canterbury region, which was critical for development on both sides of 'the hole in the hill'. By chance it also solved what had been a significant challenge for the fledgling town – a reliable supply of potable water. A spring was discovered during construction near the Lyttelton portal which delivered 60,000 welcome gallons (270,000 litres) of good quality drinking water.

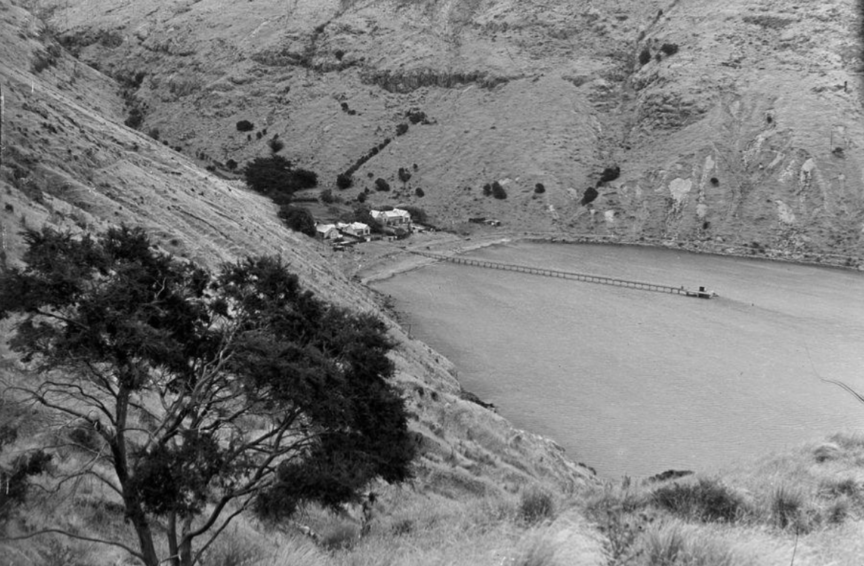

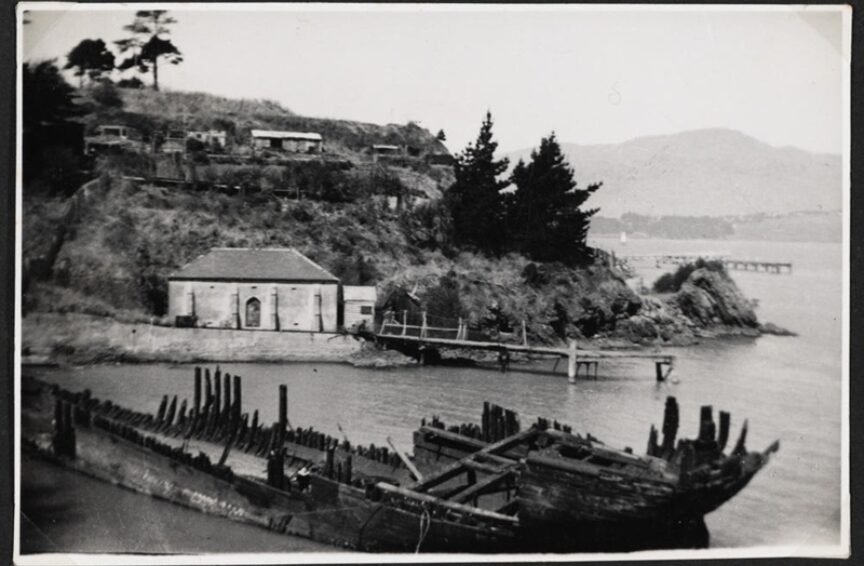

This period of work incorporated the construction of a breakwater at Officer's Point in 1865, named Gladstone Pier after the first barque, the W E Gladstone, to berth there. Situated below the bluff which from 1876 accommodated the Timeball Station, it had been a site for loading and discharging ballast since the early 1850s. With the steam dredge Erskine hard at work in the inner harbour, other major capital works undertaken by the Harbour Board in the 1870s included the 1883 graving dock with patent slip alongside, and the lighthouse erected in 1878 on the end of Gladstone Pier.

The rail tunnel and reclamation project resulted in the burial beneath mountains of spoil of the Māori fishing and trading site of Ōhinehou, which had been in use prior to European arrival, near what is now Sutton Reserve on Norwich Quay. A Māori Hostel was opened in June 1865 on the reclaimed land, intended to accommodate those whose lives had been disrupted by the reshaping of the foreshore.

This area was named Dampiers Bay by the English after Christopher Edward Dampier, solicitor for the Canterbury Association; Godley had granted him the right to 'squat' at the northern end of the attractive bay in 1850. Significant reclamation work between 1879 and 1883 saw the bay completely filled in, with Godley Quay becoming a roadway rather than an esplanade.

Another reclamation of 29 hectares at Naval Point began in 1909 and was finally completed in 1925; once the 'new' land had been left to settle and dry, road and rail infrastructure was constructed. Tanks for the Vacuum Oil and British Imperial Oil companies were built by Andersons engineering company, later joined by a boldly branded Shell oil tank. The first bulk tanker to use the facility was the Lincoln Ellsworth in October 1928. As well as diesel and petroleum, the tanks held bitumen, kerosine and in later years, jet fuel.

In 1944 Naval Point became the site of the HMNZS Tasman shore training station. The reclaimed land has also been an important local recreational area with well utilised playing fields and the Naval Point Sailing Club. Risks associated with bulk fuel storage became apparent in 1961 when a bitumen tank caught fire and again in 1985 with an oil tank explosion. The latter event resulted in some structures being moved a safer distance from the housing nestled on the hills above Naval Point.

The mud of the harbour would continue to 'swallow' huge quantities of fill over ensuing decades. From 1957 – 1964, rock from the Gollans Bay quarry was used to construct Cashin Quay container berth, and the dredge Peraki was hard at work moving the mud displaced from the seabed by these works. In the same period the Lyttelton Road Tunnel was under construction, resulting in more changes to Norwich Quay. Completed in 1964 the road tunnel provides another vital link to Christchurch and the wider Canterbury region.

Major reclamation works continue into the present day under the authority of the Lyttelton Port Company. In 2019, a ten hectare area of land was completed at Te Awaparahi, made up largely of rubble from the devastation of the Canterbury earthquake sequence of 2010 and 2011. This expansion has since been increased by six hectares with material sourced once again from the Gollans Bay Quarry. Continuing major infrastructure development between 2018 – 2020 saw the construction of a 148 m long cruise ship terminal at Gladstone Quay, which involved driving 64 primary piles 65 m into that infamous soft mud.