PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

The Leprosy Colony on Quail Island

Between 1906 and 1927 Ōtamahua Quail Island in the middle of Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour, was host to the South Island's only leprosy colony with 14 men incarcerated there. Leprosy (or Hansen's Disease, after the Norwegian doctor who discovered its bacterial source in 1873) is a disease known to humankind for many thousands of years. Prior to advances in modern medicine it was widely misunderstood to be highly infectious and in many cultures sufferers were ostracised. This was in part because it can result in disfiguring skin lesions and even loss of extremities due to injuries and infections, which a person does not notice due to nerve damage and consequent lack of sensation. Infected people also experience a decline in muscle strength and some go blind. Public fear was exacerbated by racial prejudice, especially anti-Chinese and anti-Polynesian sentiments.

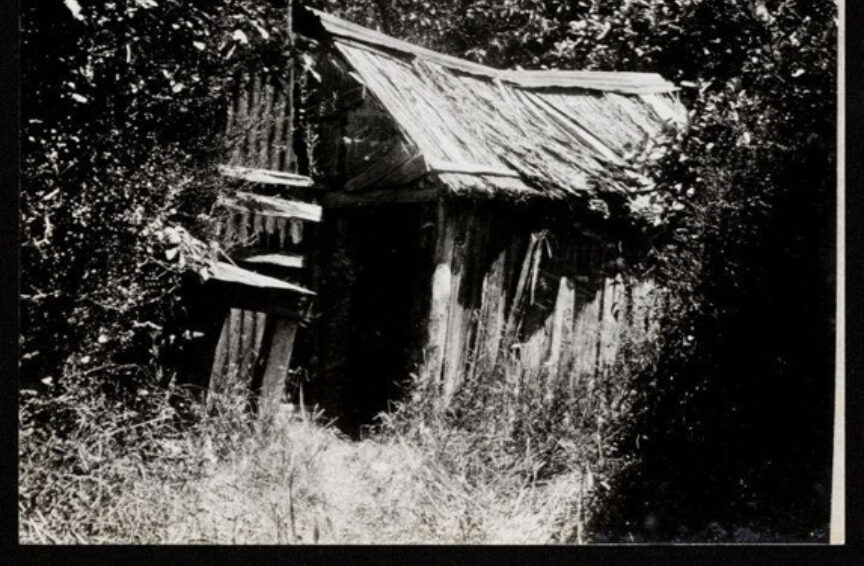

In the early twentieth century New Zealand health authorities took a similar approach to other Western countries in the management of the disease by embracing isolation practices. In 1906 the first man diagnosed with leprosy in Ōtautahi Christchurch and held in isolation on the island was Will Vallane; although provided with meals by a matron resident on the island, he spent eighteen months primarily alone with his eyesight and mobility failing. Initially housed in the barn-like old quarantine barracks, a purpose-built cottage was constructed a year after his arrival, more suitable for a sole occupant. In 1908 he was joined by a second sufferer and a third in 1909.

More small cottages were built as the population continued to grow. Although the bay (now called Skiers Bay) could be delightful in summer, it lost the sun behind a ridge as early as 2 pm in winter. The men had regular visits from Lyttelton's popular and compassionate Dr Upham, gardened and swam if health permitted, listened to the radio and kept pets (notably canaries, a parrot and the wild island rabbits, which they tamed). There were occasional church services, family visits and humanitarian delegations, with visitors keeping at least six feet away from the men; white picket fences surrounding the cottages marked the dividing line between the two groups. But their main support was each other, although the tensions arising from their situation sometimes threatened that vital camaraderie.

There is no doubt that the enforced isolation weighed upon the men, especially for those whose health was declining. A few men were released as cured; George Philips, who was declared free of the disease but required to wait eighteen months for clearance before release, could not tolerate that extra time. He absconded via Moepuku Point, arriving at Orton Bradley's house in Te Wharau Charteris Bay so convincingly dressed as a clergyman that he was able to make a telephone call and was last seen heading to Christchurch in a taxi cab, where he changed his name and disappeared from public scrutiny.

There were two leprosy deaths on the island; the most well-known was a 25 year old Samoan born man, Ivon Crispen Skelton, who died on 20 October 1923 and was buried on the headland facing Aua King Billy Island with Reverend A.J. Petrie of Holy Trinity presiding. Apparently forgotten by history, there was also 55 year old Te Iringa from Kirikau Pā on the Whanganui River, whose death and burial in 1922 were recorded in the Press at the time; Father Patrick Cooney of St Joseph's Catholic Church conducted his service. Skelton's grave was originally surrounded by a picket fence and was the subject of an archaeological dig in 2015. Surprisingly, no remains were found; it is postulated that his grave near the cliff edge was washed away in a storm. His resting place is now commemorated by a simple wooden cross, though Te Iringa's gravesite is not documented or marked.

In 1925 the eight remaining men were moved to Makogai Island in Samoa, joining 300 other sufferers and benefitting from a greater sense of community. Five of them were never to leave; including the original sole resident of Quail Island, Will Vallane. He died on Makogai in 1937 in his early 60s, having spent over 30 years in isolation. The tragedy of the long human history of leprosy is that it in fact has low pathogenicity with 95 percent of people exposed to the bacterium not going on to develop the condition. Advances in Western medicine in the 1940s mean that leprosy is curable if diagnosed early and treated with Multidrug Therapy. Nevertheless, it is still a serious disease in parts of the Americas, Africa and the Western Pacific, associated with poverty, lack of access to medical intervention and continuing misunderstanding. With the wisdom of hindsight, the Quail Island men could have been saved from two difficult decades of isolation.

See also The Dark Island: Leprosy in New Zealand and the Quail Island Colony, Benjamin Kingsbury, Bridget Williams Books, 2019.