PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

Terra Nova's Motorised Sledge

On 26th of November 1910 crowds of excited Cantabrians farewelled Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition aboard the former whaling barque Terra Nova as she sailed out of Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour bound for Antarctica. On board were 33 dogs and 15 ponies that had called Ōtamahua Quail Island their quarantine and training home for some months. Alongside them in the hold were three motorised sledges, precursors to the caterpillar tracked tanks of WW1, as well as the later Antarctic ‘Weasels’ and modern snowcats that revolutionised polar transport.

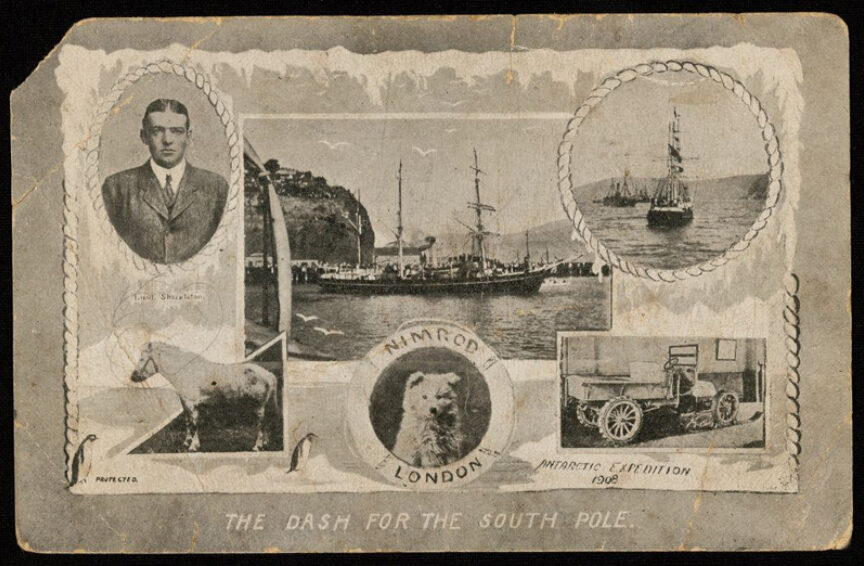

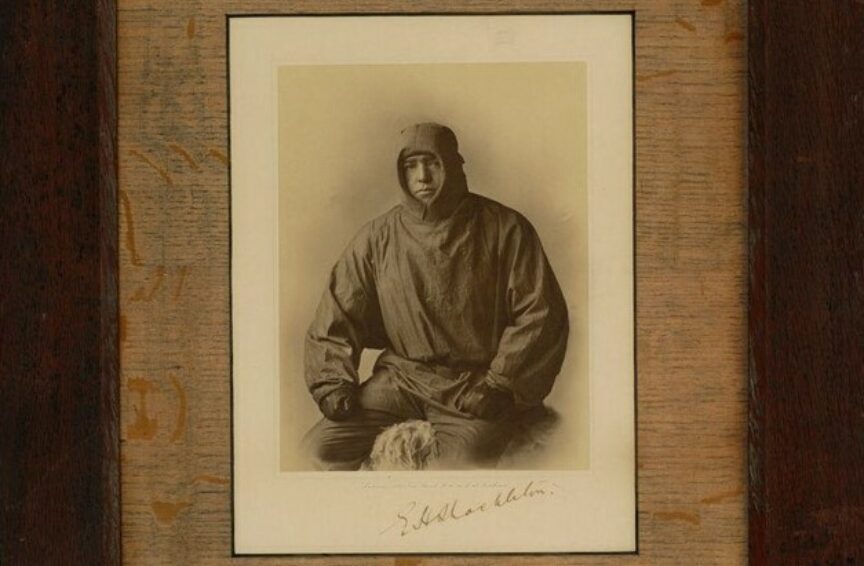

Influenced by Ernest Shackleton’s novel use of an Arrol-Johnson automobile in his ‘Nimrod’ expedition of 1907-09, Scott was convinced that motorised transport was the way of the future. With this future in mind, he had procured three purpose-built tractor sledges from Wolseley Motors Limited, a subsidiary of the British Vickers engineering and armaments company. These were heavy sledges equipped with two caterpillar tracks on dual axles, with the rear axle powered by a centre mounted four cylinder, 12 horsepower, air-cooled, petrol engine. A padded seat allowed for a driver at the back who controlled the throttle and two-speed forward gearing (no reverse gear or brakes), while the tractor was steered by a helmsman walking ahead with a steering rope to guide the contraption to the left or right. With a maximum speed of just 3.5 miles per hour (5.6 km/h) in top gear, the tractors could nonetheless haul over 1 ton of equipment and supplies on towed sledges.

Scott had also enlisted the help of the world’s first Antarctic mechanical engineer, Shackleton’s Arrol-Johnston mechanic and driver Bernard C. Day who – along with Royal Navy veteran and native of Hambledon, Hampshire, William Lashly – would be responsible for keeping the motorised sledges working in the severe Antarctic conditions. Arriving at Cape Evans in McMurdo Sound on 4th January 1911, two of the motorised sledges were set down on the ice and successfully hauled 1 ton loads up to the expedition’s base camp. Unfortunately, four days later, with the ice around the Terra Nova deteriorating, the third sledge was set down and promptly plummeted 12 fathoms deep into the frigid waters.

While Scott had high hopes for the Antarctic’s motorised future, these were quickly tempered by the constant difficulties that Day and Lashly encountered in maintaining the tractor engines. The air-cooled motors overheated on longer and heavier hauls, had problems with the oil lubricant system and frequently broke down, sometimes even requiring their mechanics to complete overnight engine rebuilds in -25 degrees centigrade! The biggest flaw, however, as was the case with Shackleton’s Arrol-Johnston, was the loss of traction on ice which then required manhauling.

On the 24th October 1911, the journey to the South Pole began with an advance supply party departing Cape Evans bound for the Great Ice Barrier (Ross Ice Shelf) and on towards the Beardsmore Glacier. Day and Lashly drove the motorised sledges towing 3 tons of supplies between them on three large sledges. After a painfully slow and arduous journey across ice taking several days, with constant breakdowns and overheating, the team became the first Antarctic expedition to drive onto the Barrier. After this initial success, however, the constant strain on the engines over the year took its toll, with both failing catastrophically on November 1 after covering just 50 miles (80 km) in 7 days. With another 150 miles (240 km) to their assigned destination, the motorised sledges were abandoned for good, with the remaining supplies man hauled across the frozen terrain.

When Scott’s team caught up with the advance party, Day was sent back to camp, while Lashly remained for the ascent to the Beardsmore Glacier and the plateau beyond. Famously not chosen for the last deadly leg of Scott’s bid for the South Pole, Lashly turned back with just 150 miles (240 km) to go. Thus it was that both Day and Lashly survived to tell the tales of their mechanised adventures in the Antarctic.

See also https://www.teuaka.org.nz/news/shackleton-sprinting-to-the-pole