PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

Arduous Journeys and Uncertain Arrivals - Assisted Migration and Quarantine

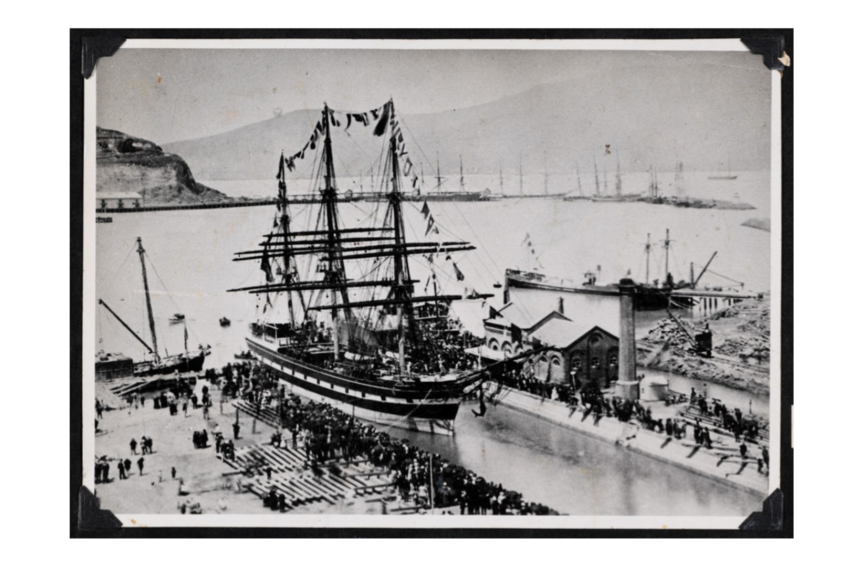

Throughout the 19th century, many courageous individuals heeded the call to leave Great Britain to sail approximately 12,410 nautical miles (22,983 km) to Aotearoa New Zealand in pursuit of a better life. Both the journey, on fast merchant sailing ships called 'clippers' due to their relative speed, and arrival in their new home, was fraught with challenges.

The first wave of organised migration under the Canterbury Association's planned Church of England settlement saw twenty-eight ships carrying 3,500 people arrive between 1850 and 1853. With the demise of the Canterbury Association in 1855, the Provincial Government took over immigration until 1870, offering some migrants financial assistance for the voyage (which was expected to be repaid in part, after settlement in the new country).

From 1870 working class British, Irish, Scottish (and a few Welsh) citizens were enticed to migrate to New Zealand by agents visiting small rural villages, selling the dream of a land of plenty 'down under'. Of additional temptation was the opportunity to have their passage paid for by the New Zealand Government. Treasurer Julius Vogel was behind a massive government borrowing programme to fund public works projects. This also paid for an assisted migration scheme to provide 'manpower' to build roads, railways and telegraph lines.

For a typical agricultural labourer in England at that time one's diet consisted mainly of bread and potatoes, with a little cabbage or bacon fat thrown in as available. Many were illiterate and there was little hope of improving one's lot in life, nor of one's offspring. The impacts of the industrial revolution had exacerbated poverty as traditional livelihoods were eroded, which meant a real risk of ending up in the workhouse. Little wonder many chose to take a perilous sea voyage, in the sure knowledge that they would never see their birthplace again.

More than 100,000 assisted migrants arrived during the 1870s, including a record of over 32,000 in 1874. The journey from England to New Zealand took about three months and individual experience on board was determined by the same social and economic strata that then characterised British society. If one was a privileged cabin passenger, there was space and the opportunity to stroll the poop deck and take part in 'entertainments'.

However for steerage passengers, shipboard life was mainly confined to the bowels of the vessel. Timber bunks, constructed in two tiers and measuring about six by two-three feet, with a canvas curtain, provided one's only privacy, rest area, and storage space. A long central table was the communal space for cooking, sewing or social activities. Washing was done in a bucket, toileting facilities were rudimentary, and rodents, cockroaches and lice abounded. Conditions were crowded, damp, malodorous and unsanitary; during storms, hatches were battened down, sometimes for many days at a time.

Given these factors, and that health clearances in England prior to embarkation were cursory, resulting in some ships having disease on board prior to departure, it is no surprise that there were deaths on many voyages. When enteric fever (typhoid), scarlatina (scarlet fever), diphtheria and/or smallpox ripped through a vessel, tolls could reach well into double figures, with especially high numbers of infants and children. Ship's doctors and the matrons assigned to single women's welfare had little capacity to minister to sick passengers. It was largely up to an individual's innate resilience whether one survived illness. Burials at sea were mostly done with minimal ceremonies.

Challenges were not over upon arrival in Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour. Immigration barracks had been erected in 1850 for the arrival of the Canterbury Association's 'First Four Ships'; they provided temporary accommodation while 'Colonists' found their feet and a place for employers to vet prospective workers from steerage.

By 1863, concerns about infection spreading to the local population were behind the provincial government's decision to establish a human quarantine station at Te Pohue Camp Bay, on a 50 acre block originally set aside for stock quarantine. It had a safe anchorage from which to ferry migrants ashore, but for the first to be quarantined there off the Captain Cook, it was just a wet and miserable 'tent city'. Seventeen had died during that ship’s voyage and another five deaths followed in the bay.

Lobbying by passengers and concerned citizens resulted in the erection of timber barracks in 1864; these structures were levelled in a storm less than a year later, testifying to the exposed nature of the site. A small cemetery on the headland was the final resting place of a probable total of 74 individuals - burials took place from 1863-1880, long after the bay stopped being used for quarantine.

Fear of the spread of disease continued to be voiced in the “Lyttelton Times” and other regional papers; in 1873, a third quarantine solution was proposed on Ripapa Island. A hospital and five large barracks capable of accommodating 300 people were constructed to architect Frederick Strout's design (this saw the disestablishment of the remains of the 1820s era pa of Taununu, a Ngāi Tahu chief from Kaikoura). Passengers from the 1873, typhus ridden, Punjaub were held there; twenty-seven had died at sea and a further eleven succumbed in quarantine (they were buried at Camp Bay). The site was taken over for use by the Government's penal authority in 1876.

A fourth and final quarantine complex was built on Ōtamahua Quail Island in 1876. Evidently it was little used for its intended purpose. Many ships were not required to quarantine; that difficult decision was the responsibility of Dr Donald, then Lyttelton's Medical Officer. He must have felt immense pressure from multiple quarters - shipping interests, migrants eager to start their new lives, and a local populace wary of infection. The facilities were used for other purposes until 1931, including during the post WWI influenza epidemic and for a Leprosy Colony.