PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

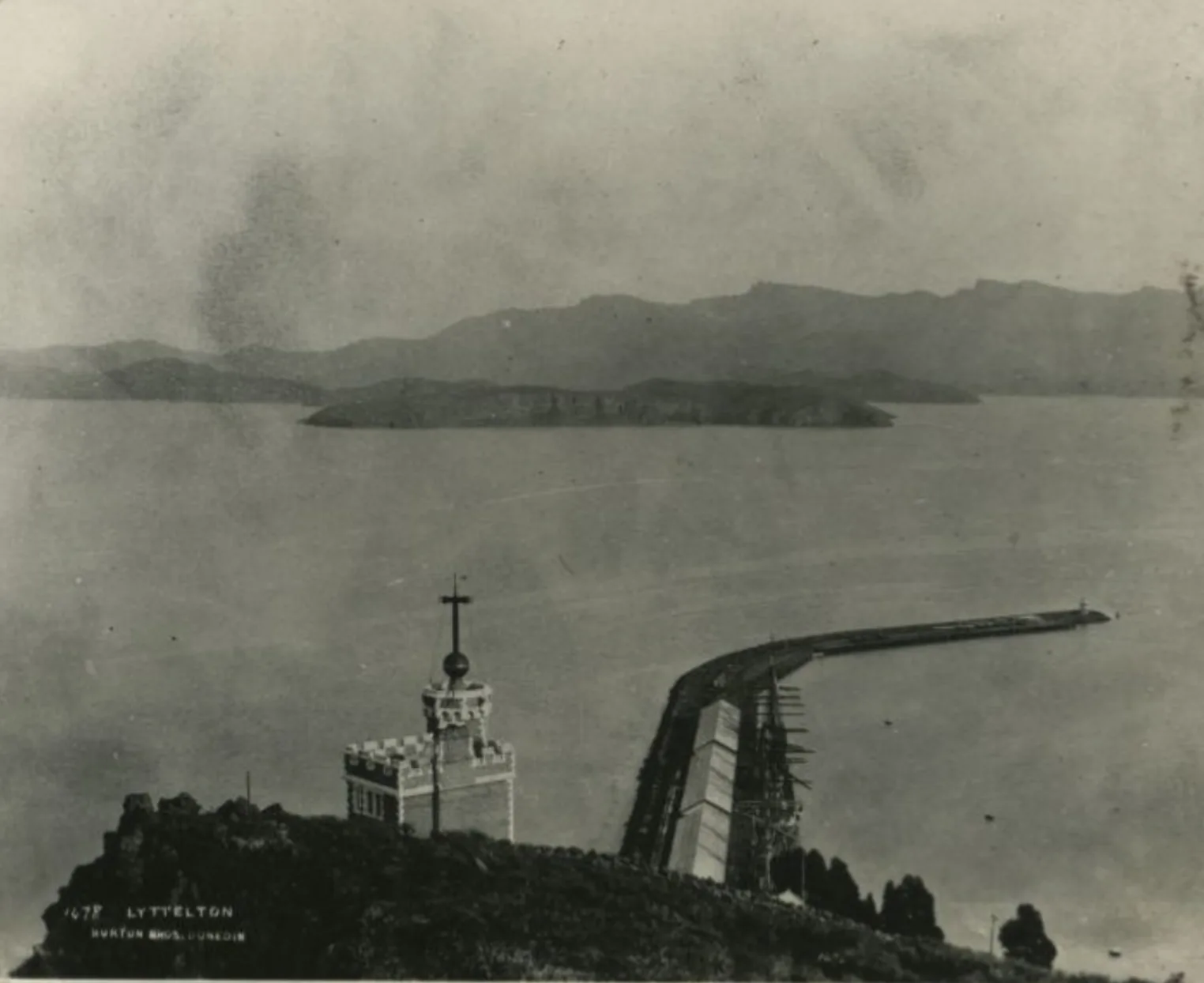

View from behind Signal Tower of the top of Timeball Station, Gladstone Pier, and Quail Island, circa 1890s.

Te Ūaka The Lyttelton Museum ref. 537.1

https://www.teuaka.org.nz/online-collection/532399

The Lyttelton Timeball Station – Part One

From its prominent position high on the ridge above Officers Point, the Lyttelton Timeball Station has been a significant landmark on the skyline since its completion in 1876. With Lyttelton being a busy port, this location was chosen in order that the dropping of the timeball and associated flag signalling could be seen from the township, inner harbour and the Adderley Head signal station at the entrance to Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour.

Albeit a well loved feature of Lyttelton’s landscape, the Timeball Station’s purpose and function is not always well understood if current anecdotal accounts are anything to go by; we aim to put that to rights here! The dropping of the Timeball at precisely 1 pm NZMT (NZ Mean Time) enabled ship’s captains to compare local time with GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) – a crucial means of recalibrating their instruments after long sea voyages, during which chronometers could gain or lose precious seconds.

In any long sea journey, accurate determination of a ship’s position (latitude and longitude) is critical – a few degrees out can mean the difference between life and death due to the risks of collision with landmasses or reefs, or other maritime losses resulting from not knowing exactly where you are. In 1800s and 1900s European sailing practice, latitude was relatively easy to calculate with the use of an astrolabe (cross staff) or sextant, which measured the angle between the sun and the horizon. Longitude posed a greater challenge; the much used ‘dead reckoning’ perhaps in part named due to the consequences of getting it wrong – ”you’re dead if you don’t reckon right”.

Lieutenant James Cook had taken an early chronometer for a test drive on his second voyage to New Zealand in 1772, resulting in the confirmation of the success of the technique. With a chronometer on board, a navigator could accurately calculate the difference between the time at a previously known fixed point and the time at his current position, thus being able to calculate longitude accurately. The development of a reliable chronometer by English watchmaker George Harrison in 1759, after 30 years effort, was the linchpin for the widespread uptake of this method of navigation. One of Harrison's clocks is housed in the Royal Observatory at Greenwich for those lucky enough to visit.

Consequently, a network of timeballs of varied designs sprung up in major ports around the globe in the Victorian era. Lyttelton’s Timeball was one of six throughout Aotearoa – Auckland, Wanganui, Wellington, Timaru and Dunedin also had their maritime timepieces, with Nelson having a noon time gun and a contemporary timeball being erected on the Whangarei marina office in the 1990s.

With Siemens Brothers apparatus, and its wooden frame covered in a zinc cladding, the Lyttelton timeball was manually wound to the top of the mast at three minutes to 1 pm each day. Originally, the drop was triggered telegraphically via the Colonial Observatory in Wellington then the Telegraph Office in Lyttelton, to the Edward Dent and Co clock in the clock room of the tower, although the ball could also be dropped manually. The moment the ball left the crossbar signalled precisely 1 pm; that time was chosen as mariners were otherwise engaged at noon - seamen changing watch and staff at observatories busy taking noontime sun readings.

This great description by George Eiby, Superintendent of the Seismological Observatory in 1978, does not however, evoke the wonderful sound effects of the old ball in action - a rhythmic clacking on its ascent and a loud woosh as the ball fell -

“The timeball is not a complicated mechanism. Before it can drop, it must be hoisted to the top of the mast and lowered gingerly on to a catch. This is done with the help of a rack and pinion driven by a handwheel. The process bears comparison with the setting of an old-fashioned mousetrap. When the catch is pulled away, the ball slides rapidly down the mast and comes to rest on rubber buffers at the bottom. The speed of the descent is controlled by a piston attached to the ball, which drives air out of a long cylinder rather like a giant bicycle pump. A tap at the bottom controls the escaping air and ensures that the ball falls quickly enough to provide a clear signal, but not so fast that it does itself an injury when it hits the bottom.”

With the rapid development of radio communications during and post WW1, official use of the timeball ceased in December 1934, after 58 years of service.

See also: https://www.heritage.org.nz/places/places-to-visit/canterbury-region/lyttelton-timeball